This is the most important and difficult piece I’ve ever written.

Content warning: suicide, depression, mention of eating disorder

In the past couple of years, I have conducted the BBC Philharmonic in concert and the Concertgebouw Orchestra in rehearsals, I have won and fulfilled one of the most coveted young conductor posts in the world (the Junior Fellowship at the Royal Northern College of Music in Manchester), I have co-organised and officiated at the funerals of my father, my grandmother and my cousin, I’ve had a second coming out as pansexual, genderqueer and polyamorous, I’ve become somewhat of an activist regarding the damaging stigma associated with HIV and PrEP, and even managed to successfully move house several times. Yet, writing and sharing this text has, perhaps, been more challenging than any of these things. More challenging, since the topic is one I have until this week never spoken about in public, and only very rarely in private, because it touches at the core of how I see myself. Until earlier this week, even my family were mostly unaware, but I am beyond relieved that they now know too, even though sharing this with them was the hardest of all those ‘coming outs’.

I was adopted from Sri Lanka by wonderful and loving Dutch parents at a very young age, grew up in Sri Lanka (and was educated at a British international school) until I was 14, and completed high school in the Netherlands. Adoption is complex and has only quite recently become better understood. It is almost invariably a form of trauma that every adopted person at some point in their lives has to come to terms with, which sometimes has deadly consequences. In my case, it caused (amongst other things) a destructive fear of abandonment and an extremely low self-image that, for a long time, made it impossible for me to believe I was worthy of love and acceptance.

On top of that, I was dealt a couple of cards in the genetic lottery that have proven to be both great assets and pitfalls. I have above average intelligence, many talents, extreme emotional sensitivity, an introverted personality, a number of neuroses, a fascination with death, as well as a non-normative sexuality and gender that do not fit in the ‘hetero male’ box that is at the centre of society.

All of these factors meant that I never felt I fit in anywhere. I didn’t know which country or nationality I most identified with (because I was Sri Lankan born, raised by Dutch parents in a British colonial environment). I was always perceived as ‘other’ by my peers when I was younger due to my being adopted or intelligent or queer. There was verbal and physical bullying and being excluded from groups I wanted to be a part of, no matter how hard I tried to conform and fit in, for much of my childhood. Throughout my life I have had to deal with homophobia, racism and other forms of abuse.

However, due to my abilities to shine and excel in academics and arts (not sports), I noticed from a very young age that this was the perfect pathway to gaining respect from both my peers and my superiors. It became a way for me to be seen and celebrated. I was a straight A student for my entire time at school and besides that I was always investing time in theatre and music. It was in those realms that I was able to express myself without inhibition, escape from the issues I was struggling with, and explore sides of me that I had to hide in everyday life. It almost goes without saying that these reasons for seeking out the arts are anything but unique.

It has always been strange to me how few people around me seemed to be able to—or want to—connect the dots of what I was presenting to the world with all the clues that were there, and see that underneath it all I was mostly intensely unhappy and often very depressed. It was hard for me that almost no-one seemed to realise that by only praising me when I achieved or performed at a high level that was in line with my innate abilities, I learned from an early age that I was only worth seeing, only worthy of respect when I was outperforming others. In other words, the fact that I was able to meet everyone’s high expectations, only meant expectations kept rising higher and I felt more and more constricted. I had to be the best possible friend, musician, lover, scientist—in fact, I believed that the only possible me was the perfect me who never slipped up and never dropped below an incredibly high bar.

Earlier, I mentioned low self-worth and the belief of having to earn love, rather than deserving it to begin with, and always being afraid of losing it. Throughout my life, starting around 20 years ago, there have been several long spells in which this achievement- and relationship-related low self-worth became so destructive and all-encompassing, that I saw no other way to break the cycle but to end my life altogether. While still in middle school, I realised I wasn’t straight, which caused many years of soul-searching and fighting inner enemies, as well as external bullies, in a conservative and religious environment. In my early twenties I had many adoption- and identity-related depressive episodes, as well as attempts to find a kind of love that conformed to what society traditionally expects of us, only to fail and fail again, fuelling my fears of abandonment and of being unworthy. The worst, and—I can now emphatically say—the last of these spells, happened during my first year at RNCM.

At the start of that academic year, in the autumn of 2015, I had the single most difficult breakup and rejection I had ever had to deal with, one that shattered me completely and brought me to the very core of the issues of self-worth I had been dealing with all my life. At the same time, the full force of the RNCM Junior Fellowship was coming at me, with all the high expectations everyone had of me in that position, and the thrilling and validating feeling that winning such a high profile audition had given me. I realised that despite this breakup and the ensuing suicidal depression being harder for me than anything I had ever faced until then (this includes losing two close family members a year before!), a breakup felt like the weakest possible excuse to let the high standards that had been set slip. Imagine if I had said to people: “Sorry, I’m not well prepared for this rehearsal, I’m having a difficult breakup.” Then, in January of that same academic year, my beautiful queer cousin ended her own life as a result of anorexia and depression, sending my family into the vortex of incomprehension, grief, anger and guilt that I had almost caused them to go through myself, several times, in the past. However, at the same time, her suicide triggered me even more to see death as a way to end my own spiral, and I envied her courage for choosing it.

In practice, I only cancelled one of my obligations at RNCM, so I could help organise and officiate at her funeral. After that I simply carried on. Inside, my world was dissolving and I doubted I would survive the rest of the academic year. But on the surface, all that people saw was a Junior Fellow who seemed a bit chaotic, less focused, and didn’t answer his emails as quickly as they were used to. Some people got very angry with me for not being communicative and professional enough, despite most of them knowing, at the very least, that I had suddenly lost a family member in January. They said things about my unprofessionalism and about how the show must go on somehow. Maybe some others watched me and found me perhaps a little disconnected from my music-making, a little less engaged. But all in all, no-one (apart from the very few people I confided in) really seemed to notice that anything was really amiss, because in general, I didn’t significantly drop my standards.

What should I have done? When does any of this become ‘an acceptable excuse’ in a world that is so competitive, so performance-driven, so easy to lose your place in—when you are fully aware of the fact that things could have been much worse in your life, that you had been somehow ‘spared’ or ‘saved’ (by being adopted, by your privileges, by your talents) and that you should be grateful, not sad? That you would disappoint so many people by slipping up? Maybe I should simply have answered, “I’m sorry my not replying to your emails/questions/requests sooner has annoyed you. I will try harder not to disappoint you, but I’m currently depressed and I would rather be dead. Best wishes, Manoj.” But I didn’t do that.

My life would have been a lot easier if I had felt that I could say to people I looked up to that I was having a hard time, and that their expectations were part of the problem, without feeling like I would lose everything by doing so. In fact, we need to open up this conversation much more often, in professional situations, in schools, colleges and universities, and also at home. Mental health is still a huge taboo, even though so many of us struggle with it. A big part of why it has been so hard for me personally is that as a person and as an artist I felt I was never allowed to falter or to be perceived as weak, as I had ‘so much to offer’ and all I needed to do to earn ongoing respect was to simply ‘keep up the amazing work’—already from a very young age.

Earlier this year, I celebrated my 30th birthday. I specifically say ‘celebrated’, because to me not every birthday has felt that way. On a more personal, private level, I was celebrating something more than just another year. I was celebrating that I had reached an age that I, for many years, had not expected to ever reach. So what saved me? What changed me forever?

The environment of the RNCM and the city of Manchester definitely played a huge part in all this. My experience at past educational institutes, in comparison, felt like less connected, less open-minded, less open-hearted than what I encountered at the RNCM. I felt that I could finally become me, with all my quirks and my queerness, rather than fit into a box of what is seen as ‘masculine’, or ‘normal’, or ‘strong’, or ‘authoritative’. Without realising it, before coming to RNCM, I had allowed myself to be pushed in boxes of what a conductor should be, rather than defining what a conductor could be in the 21st century by simply being who I was, with all my strength and uniqueness. I am fortunate to have had friends throughout my life whom I could confide in and talk to, could text and ring up even at very impractical times and they would drop what they were doing and attend to my needs. One of them quite literally managed to prevent me from taking the exit route once in 2016, and that was one of several pivotal moments that same year. I talked to mental health professionals, both within and outside of the colleges I studied at, some of whom were amazingly helpful and life-changing, some of whom were not. The RNCM and its welfare team, its student union, and its general open-minded atmosphere kept me going and reminded me in many ways how important it is to nurture deep social connections, and how important it is to regularly unwind and stop achieving for a while. There, I felt that space was given to people to forge their own paths and to do things on their own terms. I also read endlessly—books and online resources about mental health, about being queer, about being polyamorous, about attachment styles, about adoption, about mindfulness, trying to find ways for me to help myself when I felt I had exhausted all the other resources available to me.

I somehow began to finally learn from mid-2016 on that the evil voice in my head telling me I was worthless was wrong, and I somehow found a new voice and an inner strength that was slowly managing to stand up and overpower that evil voice. That strong, resilient voice was echoing all the things that people around me—family, friends, teachers, peers—had been telling me all along, but it was only until I fully realised that I needed to start telling myself those things and believing them that something slowly shifted. I had hit rock bottom and came through at the other end knowing it will never be as hard as that again, because I have realised I can simply be me and that is enough, regardless of how much I achieve and regardless of how many people want to connect with me at the deepest level. A true paradigm shift for me, for which I am so grateful, and which has led to much of how I now see myself, my work, my goals and my relationships—but that is another story, for another time.

If you learn anything from what I have written here, let it be this: please be mindful of the fact that people who choose a life in the arts, most likely have some difficult and dark parts to themselves that the arts allow them to process, to channel, and give a voice to. Please be aware that it is the sensitive, the thoughtful, the queer, the different kids who feel automatically at home in the expressive and beautiful environment that the arts can be, but this doesn’t mean they are therefore less vulnerable once they are in that world. Please be especially wary that achievement, and the pursuit of achievement, in any field, can become unhealthy and dangerous, when it is actually a way to fundamentally validate one’s existence. Please realise that even the high fliers, like me, who seemingly sail through the biggest challenges and keep surprising themselves and others, may be battling demons that could potentially kill them. And for those high performers, the stakes are so high that even a slight slip up can feel like a plane crash, so they keep going, because they happen to be able to do so, but at great personal cost.

I want to strongly emphasise that people who don’t manage this same change, who don’t climb out of this darkness even a little bit, should not be judged as if they have somehow ‘failed’. They may be battling even greater demons than I was, they may be ill, they may have been dealt less fortunate cards than I was, they may have been through other unfathomable traumas. Please, never use stories like mine to invalidate the fact that for some people the only way out is out, and it is a hugely courageous and difficult decision, however powerless and sad it makes us feel. Every struggle is unique, and not everyone is able to heal—as Queen Máxima of the Netherlands bravely and truthfully said recently, in her first public speech after she lost her sister to depression.

We need to raise up, support and cherish those people who are battling demons and still choosing life, and respect those who choose to end it. But the first step to helping everyone battling with mental health in some way is for all of us to acknowledge that these problems exist, they are ubiquitous, they are part of society and part of being human, and we must always create space for these issues to be talked about. My, and many other lives, would have been easier if these issues were less taboo and less seen as a sign of weakness. Also, importantly, we need to abolish the toxic system that mindlessly glorifies and commercialises an artist’s suffering because of the beauty and impact of the art their suffering ‘produces’.

The reason I have chosen to finally speak out about my personal journey is because I have experienced through the years how much I have been inspired and helped by hearing and reading about other people’s paths and challenges. I salute and thank all these brave people who have been so open with themselves, and with the world, so that their stories could reach me. I believe it is time for people with power and with impact to realise how little things they say or do can have huge consequences, both great and terrible, and this can only happen if more of us speak out and/or realise that we have this power too.

I want to conclude by sharing two of my favourite quotes.

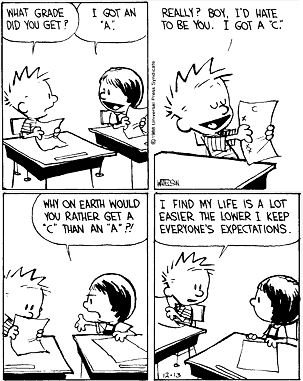

The first is from my favourite comic strip, Calvin & Hobbes, which seems to have a comic for just about every situation:

The second quote is by the late Sir Colin Davis, from an interview with the Guardian in 2011. He says, about music making and musicianship:

Maybe the absence of ego is one of the great joys that is available to us: the chance that music gives you to climb out of the prison cell of your ego and be free for an hour and a half.

I would like to add one final thing to his beautiful words: let all of us do our very best to make sure that music and the arts do not themselves become a prison.

Thank you for reading. Please share if you feel people around you would benefit from reading this. And feel free to comment and message me if you wish, provided it is done with sensitivity. I may be healing, but the scars are a part of me as well.

If you or someone you know is (possibly) suicidal, please talk to someone about it, ask for help, and/or take a look at https://www.befrienders.org for resources and people that can be contacted.

In Nederland kun je altijd bellen naar 0900-0113, of op www.113.nl kijken.

Some of the resources that have helped me and may help you too (or which you could recommend to people working through issues of their own):

- Calvin & Hobbes, by Bill Watterson; my single favourite comic strip (can be found online at www.gocomics.com/calvinandhobbes)

- www.morethantwo.com, an amazing online resource (and a book) about self-esteem, love, jealousy and polyamory by Franklin Veaux & Eve Rickert

- ‘Attached’ by Rachel Heller & Amir Levine, a book about attachment styles, how they work, how they originate and how they can be handled with sensitivity and compassion

- ‘Straight Jacket’, a mind-blowing book by Matthew Todd about what it means to grow up gay/queer in the age of treatable HIV and online dating

- ‘Together Alone: The Epidemic of Gay Loneliness‘, an article by Michael Hobbes addressing mental health among gay men that went viral because of how much it resonated with so many

- ‘Daring Greatly’ and ‘The Gifts of Imperfection‘ by Brené Brown, about finding strength in being vulnerable, and learning that simply being who you are is enough (also watch her TED talks on YouTube)

- ‘RuPaul’s Drag Race’, a revolutionary TV show which, despite all its flaws, has been instrumental to me and so many others in showing how it is possible to embrace and celebrate all aspects of yourself, not just those that society deems ‘normal’

- ‘Quiet’ by Susan Cain, who shows introverts countless ways of embracing their introversion and knowing what they need to be happy, rather than trying to change who they are

- This video by opera superstar Joyce DiDonato, in which she talks about resilience, courage, keeping the faith and realising that choosing to change one’s path is not a sign of weakness. Her entire YouTube channel is amazing: it’s so important that someone in her position is being so vulnerable and talking about all the difficult and challenging aspects of this career.

- Full interview with Sir Colin Davis in The Guardian